Why the Five Stages of Grief Theory Is Wrong

What you can really expect your grief journey to be like

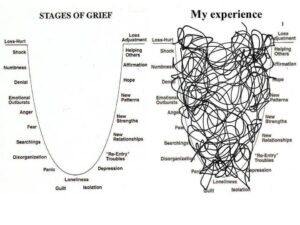

You’ve probably heard of the five stages of grief. But did you know that they don’t represent the full complexity of grief? From pop culture to mass media, countless conversations about grief talk about navigating these five steps: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. But the reality of grief is far more complicated and nuanced than that. The five stages of grief might be part of some people’s grief journeys, but they don’t apply to everyone. The idea that we all go through these famous five stages is a myth about grief.

Despite research that shows that the five stages of grief aren’t inclusive, the idea permeates our cultural understanding of grief. Many of us still expect to go through each step when we experience a loss. If and when we don’t, it can feel confusing and overwhelming. We might ask ourselves, I’m supposed to feel angry, but I’m just sad all the time. What’s wrong with me?

Nothing is wrong with you. It’s normal to look for guideposts that help illuminate our grief path. Systems like the five stages can help us feel less alone. But they can also make us feel like we’re not grieving “correctly.” In this post, we’ll explain where misconceptions about the five stages of grief come from. Then, we’ll explain what you can expect. It might not be as cut-and-dry as five distinct stages, but it also is something that doesn’t have to be so unknown and frightening.

How did we come to believe that grief happens in five stages?

It started in the 1960s when Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a psychiatrist based at the University of Chicago, decided to research something nobody was talking about: death and dying. Death is still a difficult and taboo topic, but in the 60s, the stigma was even more extreme. Doctors didn’t even have to tell patients or their families that they were dying.

Kübler-Ross conducted interviews with people who were facing death to learn more about how they were feeling and the kind of support they needed. She turned what she learned into a seminal book, On Death and Dying, which kicked off the popularity of the five stages of grief.

In her book, Kübler-Ross named each chapter after some of the common emotions she saw in dying patients—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. She went on tour to give talks about her work, and also divided her speeches into these concepts. But they were never intended to be a rigid, step-by-step system. Kübler-Ross wanted to help people put words to the emotions they were feeling, during a time when feelings about death were just not talked about.

Even though Kübler-Ross wrote her book about people who were dying, people who were grieving connected to the stages. They also needed words to anchor their overwhelming emotions. That was the beginning of how the five stages of grief became such a popular benchmark.

It’s very possible that when you’re grieving, you will experience denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. But some of those emotions, particularly denial and bargaining, are more relevant and ubiquitous in people who are dying themselves. Some emotions, like regret and longing, are extremely common in grief, but aren’t part of the five stages.

You might really connect to the five stages of grief, too. But they aren’t prescriptive or necessary to grieve “properly.” The only correct way to grieve is to acknowledge, make space for, and feel your emotions, instead of ignoring them.

If grief doesn’t occur in five stages, how does it happen?

People who are grieving are drawn to the five stages of grief because grief is so powerful and painful, and we want to feel a sense of control over the process. We want to put words and structure to our suffering. That’s why we want answers to questions like “When will I start to feel better?” and “What am I supposed to be feeling?”

Grief is personal and specific. So on one hand, the path it takes is unique. Some people grieve right away, and their feelings become more manageable after the first six weeks or so. Some people experience months of shock. Others don’t cry for the first months or up to a year. So much depends on the relationship you lost and the nature of the loss. Was it sudden or expected? Was the death natural or violent? Everyone’s personal experience of grief is also influenced by their culture, belief systems, and stress reactions.

It might feel daunting and lonely to consider how individualized grief can be. But this doesn’t mean you are on an island without any information to anchor you in your grief. Scientist Hilda Bastian analyzed over 100 studies on grief and found that for most people, and most deaths, their grief is most pronounced for a few weeks and then gradually subsides from there. That doesn’t mean it’s always linear—holidays, anniversaries, or hearing that one special song on the radio can all trigger a period of intensified grief.

With losses that are more significant or traumatic, you can expect the intensity of your grief to shift within six months to a year. Again, that doesn’t mean it’s linear. You might feel more capable of socializing with friends again in the eighth month, and then return to a period of deep sadness and withdrawal once it’s been a year-and-a-half.

There’s a fine line between having expectations about grief and prescribing that your grief needs to be a certain way. One thing that can help is seeking out support and resources from others whose grief is more similar to yours, like if you were a caregiver for a parent with Alzheimer’s or you lost a sibling in a sudden manner. Instead of connecting to this broad myth of five stages, you’ll be more likely to relate to what people in similar shoes have experienced.

It’s helpful to seek out some information about your grief and loss, because expectations help give us hope: it won’t be this way forever. Expectations also help us realize when we need extra support. If it’s been three years and you’re still having a hard time getting out of bed on a regular basis, you will know you need some extra mental health and social support.

One of the most appealing things about the five stages of grief is that they help us know we are not alone in our emotions. They reassure us that our emotions will evolve. We will all experience different feelings and intensities of grief. But when we shift our expectations from a rigid set of five stages to a more nuanced, realistic understanding of our own particular grief, we can be gentler and more compassionate with ourselves on our journey.