A Soft Landing: The Real Experience of Being a Caregiver

A Conversation with Connie Baher on the Grit and Grief of Caregivers

At the Heart of It

• Caregivers often feel exhausted, isolated, and unrecognized. It’s normal to feel anger, resentment, and guilt as a result of the stress of caring for another.

• There is no such thing as “perfection” in caregiving. This is a unique experience that can be challenging, but meaningful. Your best is good enough.

• We have many tools to reach for as caregivers, like support groups, self-care strategies, and educational materials.

Often we talk about caregiving as something noble. But what is it actually like to be a primary caregiver for another person? What kinds of grief do caregivers experience, and what happens when the caregiving stops?

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to chat with Connie Baher, author of Family Caregivers: An Emotional Survival Guide, about her experience with caregiving, and what her research has found to be true. Our conversation revealed some truly eye-opening insights into the specific challenges faced by those who care for a loved one.

Read our interview with Connie below:

HoH: Hi Connie, thank you so much for giving us a bit of your time. I have your book, and it looks like a really candid collection of people who have shared the experience of caregiving.

Connie: Yeah, that was sort of the idea, was to try to talk about the tough side of caregiving, but at the same time about the meaningful qualities of being a caregiver without being, you know, super Pollyanna about the whole thing.

HoH: What nuggets of truth do you have about caregiving, and about the grief that accompanies that?

Connie: What I found is you have two kinds of caregiving. One is acute, where something happens, all of a sudden it’s like a maelstrom. It’s like a tsunami, and it’s horrendous—but it’s short.

But then there’s what I went through with my mother, which is what I call long-haul caregiving. It’s a marathon, and it grinds you down.

Everybody has some relationship to caregiving. It’s fascinating to me. There have been studies where they ask people to describe their experience as a caregiver. The number one thing that comes up is being exhausted and depleted. And I have found that caregivers often feel invisible, and isolated, and unrecognized.

HoH: Can you tell me a bit more about that?

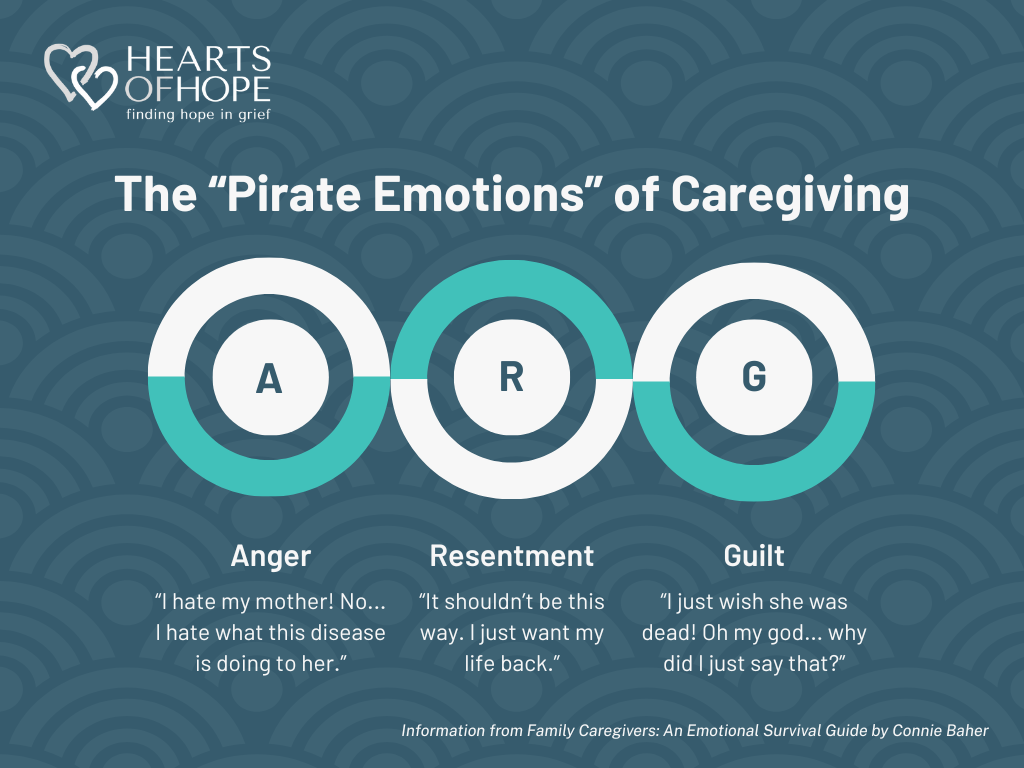

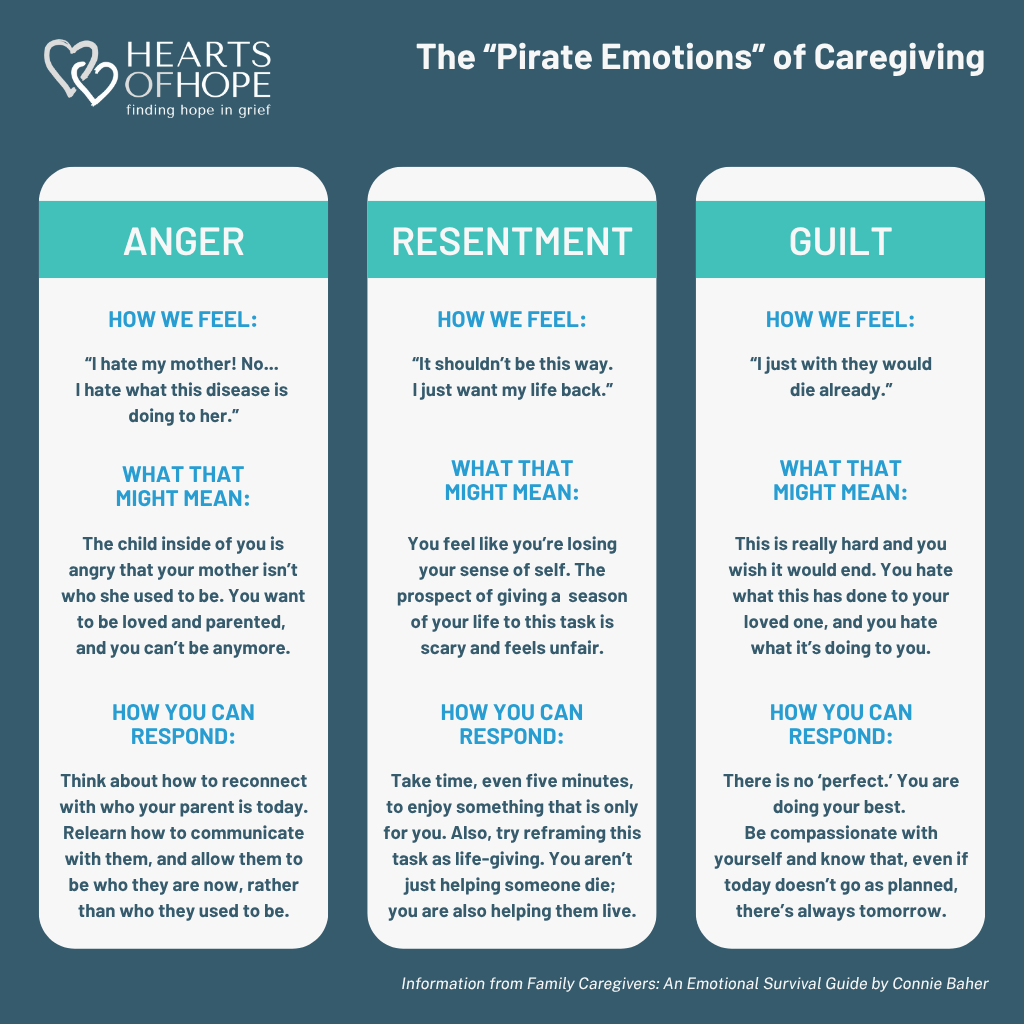

Connie: I talk about the Pirate Emotions. You know, pirates, they have their eye patch, and then they have a parrot on their shoulder, and they go “arg!” A.R.G. stands for anger, resentment, and guilt.

Connie: So, “A.” You feel angry. Why is this happening to them? You’re angry that it’s there, and you know, you could be angry at a disease, or angry at losing your lifestyle.

And so that blends over into the “R,” which is resentment. You go in each day, and you go to knock on that bedroom door and think, “oh, God. What now?”

And then you feel guilty that you feel that way. The “G.” You think, how could you possibly feel resentful and angry at this lovely woman who gave birth to you that you owe so much to?

HoH: That is fascinating, and very specific to this unique experience. Are there any other types of grief those in caregiver roles face?

Connie: Well, there’s sort of two griefs, right? There’s the grief for the person that you knew. And then there is this person who is losing cognitive function, or just becoming more frail. A lot of people sort of recede from life as they’re nearing their end. And so that’s the new reality. And that’s the person that you’re also going to lose.

Many caregivers also experience feelings of inadequacy. Why? Because you’re faced with [someone who’s in decline.] As people get further into dementia or advance in age, they can get kind of nasty, and they’re not appreciative of what you’re doing. So that can make you feel all the more inadequate. You know, you’d like to go in, and you’d like them to leave them with a smile. Well, occasionally, some days that works, but some days, maybe not.

Another challenge is that, as a caregiver, you can feel like you’ve lost your sense of identity.

But you know, you can’t be perfect. There’s no such thing as perfect. Life is messy, and [you’re trying.]

Let me give you a phrase that a friend of mine she’s what I call a “serial caregiver,” because as soon as she finishes caring for one friend, a few months later, she’s found somebody else.She must have cared for five or six people at the end of their lives. I asked, “Why do you do that?”

And she said, “It’s because I want to give them a soft landing.”

HoH: What about after the caregiving ends? Often, of course, the end of that role comes hand-in-hand with a grief event. How do caregivers feel about things once they stop caregiving?

Connie: People talk about how stressful it is, especially the long-haul caregiving, but I’ve found that after the caregiving ends they look back and they often see something else. They say, “It gave me purpose.”

I hesitate, though, to think that it’s a blessing, because that kind of makes it sound like, “Oh, how wonderful!” It’s not wonderful, but it’s a unique experience. And if you can get through it, it can be transformative. It stays with you. It’s a good thing you’ve done as a person on this planet.

HoH: That is really such a unique experience. What a connection to have with someone else. Thank you for sharing that. For those who are currently caregiving for someone, what tools can they find for working through their situation? How can they move through this season in a healthy way?

Connie: First, build a team to support you. So, chaplains, palliative care doctors, social workers. AARP has tools, Catholic charities have tools. Support groups can be tremendous. Not that anybody can suddenly make the difficulty go away, but often people just need to let it out. You want to connect with people who are delivering a level of care that is one stage beyond yours. There is a lot of support out there, and as others become involved it can be helpful, because there are others who are trained to help in various ways. Don’t fly solo.

Secondly, When you’re a caregiver, you need to be on-call 24/7. But I try to remind people to nurture some small corner of something they love to do. Watch ten minutes of a movie, read a book, play a musical instrument, anything, because you’re going to need something to build on when the caregiving ends.

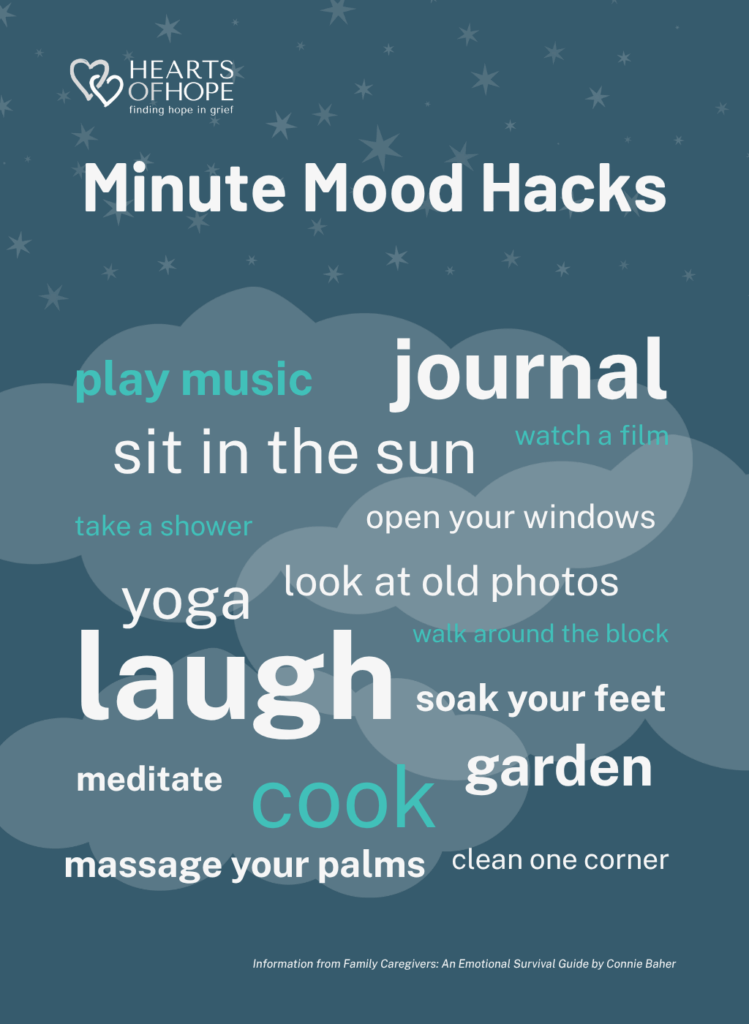

Finally, I’ve done a number of programs called “How To Take A Break When You Don’t Have Time To Take A Break.” I call them Minute Mood Hacks.

I know you don’t have time to take a three-day spa weekend with your friends. I know that. But maybe you learn to do some sort of little self massage. Just a couple of minutes, of something that gives you some sort of pleasure.

I think it was [Hearts of Hope Founder] Judy who said, you know, you wake up some mornings and think, “oh, my God! Here comes the tsunami of everything that I have to do.” But you know what? Give yourself five minutes to stay in bed. Give yourself a sense of control. For just those five minutes, life will carry on.

Pause for a Beat

• Have you or someone you know provided primary care for someone, even temporarily? Did you experience the A-R-G “Pirate Emotions” Connie mentioned?

• We spoke about the importance of “letting it out.” Make a list of people or groups you might be able to speak freely with about caregiving and how it affects you. You could even journal about it.

• What are a few quick, one-minute things you can do to reconnect with yourself?

Hope and Healing Toolbox

- The National Institute of Ageing has a lot of resources for caregivers and their specific challenges

- Read Connie’s book for more insights and tips: Family Caregivers: An Emotional Survival Guide

- After caregiving is over, try our workshop Moving Forward, or read our blog about what to do when your loss isn’t recognized

- Need to “let it out?” Drop us a message any time. We’re here to help.

Connie Baher writes, lectures, and coaches on caregiving, life transitions, and reimagining retirement. Published in USA Today, The New York Times Magazine, Forbes, Dow Jones’ MarketWatch, the Boston Globe, and other print and online media, she is the author Family Caregivers: An Emotional Survival Guide and The Case of the Kickass Retirement: How to Make the Most of the Rest of Your Life.

She is a Harvard MBA, entrepreneur, former tech executive, and long-haul family caregiver. An award-winning lecturer, she has served on the faculty of The Honor Foundation, a career transition program for Navy Seals and Special Operations personnel. She has worked extensively with nonprofit organizations and received a Royal medal honoring her work with cultural organizations in Cambodia.

She and her husband live in southern California. Connect with her at conniebaher.com.